Given the volatility in the markets, I’ve decided to start occasionally posting some investing notes. These will sometimes be on individual companies, and sometimes on more asset allocation-related things. None of it will be a recommendation to buy or sell anything, but it’s something that I hope will add value to subscribers that either invest your own or other people’s capital.

Almost all of these posts will be for paid subscribers. But we’ve made this one available to all readers. The first of these notes was posted last month.

Disclosure: I am a portfolio manager at Sorfis Investments, LLC (“Sorfis”) and clients of Sorfis may own shares of stock in a company or companies mentioned in either the post below or links associated with the post below. I may in the future buy or sell shares for myself or clients and am under no obligation to update those activities. This is for information and entertainment purposes only, and is not a recommendation to buy or sell a security. Please do your own research before making an investment decision, or consult a qualified financial advisor.

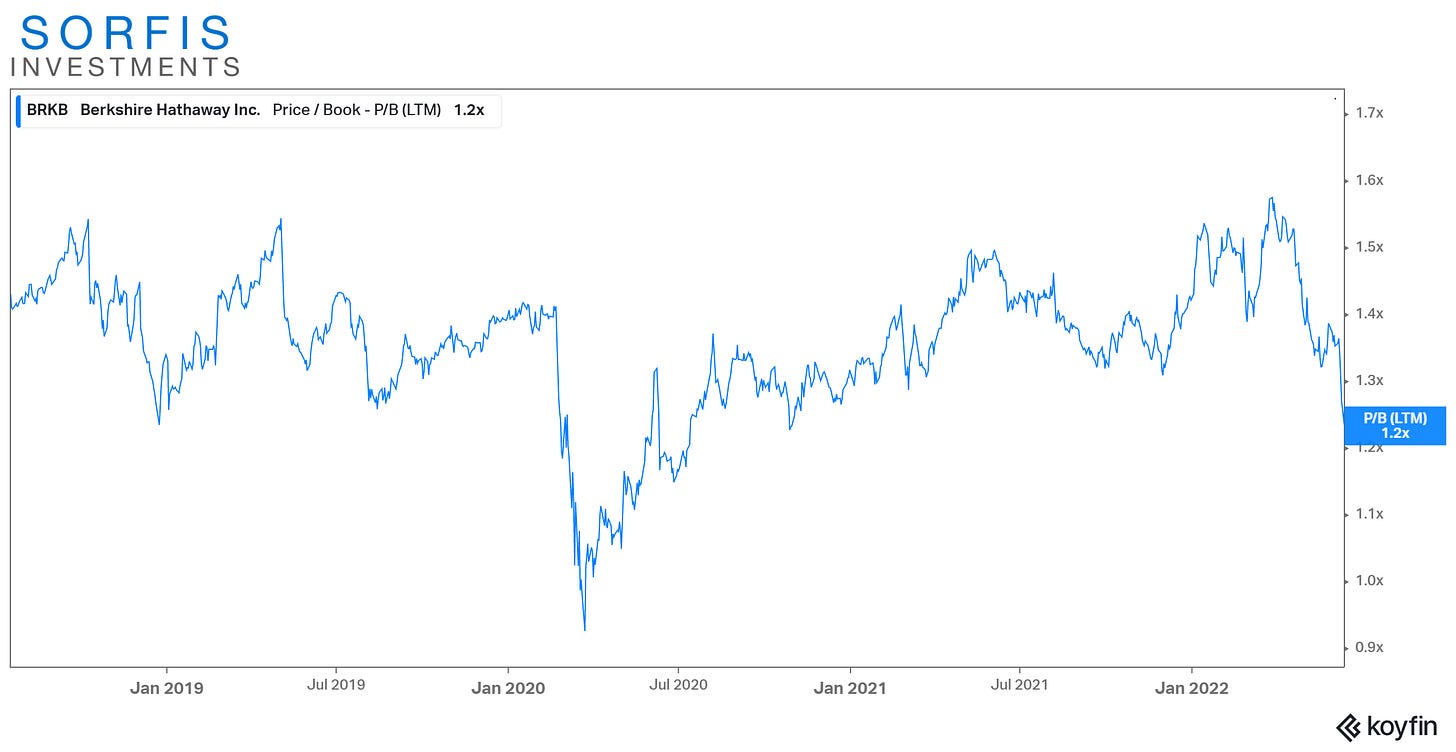

Berkshire Hathaway is back around 1.2x its last reported book value, and is still well below 1.3x even if one takes the Apple position down a bit to account for something closer to a 20x P/E ratio on Apple’s valuation. Generally, buying below 1.35x has turned out well in the years that follow.

We know that Berkshire was buying back a lot of stock just north of $300 per B share, so it’s likely they are buying back here too (it closed at $281.56 today). Berkshire changed its repurchase threshold from 1.1x book value to 1.2x in December 2012, and then eliminated the threshold altogether in July of 2018:

The Board of Directors of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. has today authorized an amendment to Berkshire’s share repurchase program. The earlier share repurchase program provided that the price paid for repurchases would not exceed a 20% premium over the then-current book value of such shares. Under the amendment adopted by the Board of Directors, share repurchases can be made at any time that both Warren Buffett, Berkshire’s Chairman and CEO, and Charlie Munger, a Berkshire Vice Chairman, believe that the repurchase price is below Berkshire’s intrinsic value, conservatively determined.

Other than the brief Covid-lockdown drop, it’s back down around the lower end of where it has traded on a P/B basis since making that move:

And THIS CHART is even more useful. It was posted by the user ‘mungofitch’ on the Motley Fool Board, who seems to have been dishing out useful information on those boards since 2001. The data hasn’t been updated since March, but it gives one a good idea about good times to buy, or possibly trim back, Berkshire over the years. And the current valuation would fall right along the blue line in the chart.

As always, if you want to go deep on Berkshire, check out Chris Bloomstran’s letters to shareholders.

Speaking of the aforementioned mungofitch, he also recently made a case that QQQE (Equal Weighted NASDAQ-100 ETF) might be worth looking into:

I have a few different models using slightly different assumptions (different mounts of history, more conservative trend lines, average rather than median etc).

I just redid those models, and get figures in the range $62-72.

With the price at $65, the indication is that it's not [particularly] overvalued, nor particularly undervalued.

Why is this an investment worth considering?

* It can't go bust.

* The rate of growth of value is astounding. With the trend line above, earnings have risen at inflation + 8.2%/year. Plus you get about 0.5% dividend yield.

* It's a simple one-step purchase.

In today’s big down day in the market, QQQE closed at $61.96.

S&P 500 Expected Returns

Let’s break down the components:

Sales Growth per Share

Dividend Yield

Change in Profit Margin

Change in Multiple

As the Chris Bloomstran letter mentioned above showed, sales growth per share has been 3.7% over the last decade, and about the same over the last two decades—with 3% of that from sales growth and 0.7% from buybacks. With more debt on corporate balance sheets, a shaky global economy at hand, and (probably) less monetary and fiscal support for a while due to inflation, it’ll probably be difficult to match that, so let’s assume that it stays about the same.

The dividend yield is about 1.55%.

So Sales Growth per Share plus Dividends gets us to about 5.25%.

Profit margins likely peaked at the end of 2021, which seems especially likely given the profit warnings we’ve seen from companies lately and inflation likely to bring margins down. Best case, we can assume they stay about the same.

Market multiples have now re-rated quite a bit. They reached all-time highs on almost every valuation measure at the end of 2021, and are still near or higher than any previous market top on most measures. So it seems, even with a lower multiple than when we started this year, the change in valuation multiples going forward is likely to be more of a headwind than a tailwind.

Most of the popular valuation metrics have the market still needing to fall 20-40% to ‘revert to a historical mean valuation.’ So fair value seems like it may be somewhere in the 2,400-3,000 range on the S&P 500 (again, assuming we actually revert to the mean on those measures, which may still require higher interest rates).

Someone smart that I was listening to recently on a video or podcast [it may have been the Druckenmiller video] mentioned that with inflation above 5%, we’ve always had a recession and profit margins tend to fall about 35% on average. Given the current multiple now seems reasonable on the S&P on trailing earnings, a 35% drop in profits on that same multiple gets us to about 2,437 on the S&P 500, so that’s in the same ballpark as the above.

John Hussman also had some relevant math in the Market Comment that he released a couple of weeks ago:

The current price/revenue multiple is 2.6. Though it’s down from 3.2 at the January peak, it’s also at a level that was never seen in history prior to August 2020. Meanwhile, market internals remain ragged and divergent, suggesting risk-aversion among investors. That combination creates what I’ve often described as a “trap door” situation. The S&P 500 dividend yield is presently less than 1.6%, and the growth rate of revenues even since the 2009 market low is less than 3.8% annually. Even if we assume that valuations and profit margins will be 50% higher than their historical norms forever, that would still put the valuation norm at 1.5 x revenues, more than 40% below current levels.

What if it takes a decade to touch that level, without ever breaking 1.5 x revenues?

Average annual total return: (1.038)*(1.5/2.6)^(1/10)-1+.016 = 0%

***

Well, let’s be optimistic and ignore historical norms altogether. Let’s assume that the price/revenue multiple never drops below the average level of 1.8 we’ve seen during the bull market advance since 2009, and also assume that revenue growth averages 6% annually. Given the current 1.6% dividend yield, where does that leave a 10-year total return estimate?

Average annual total return = (1.06)*(1.8/2.4)^(1/10)-1+.016 = 4.6% annually.

Wait. I thought we were being optimistic.

We are being optimistic. But remember, even a market that virtually goes nowhere for a decade can go nowhere in an interesting way. There will certainly be periods when market internals improve, and even rich valuations may be associated with reasonable opportunities to embrace market risk, within limits. The lower valuations get, the more aggressive the investment response can be. Both the 2002 and 2009 lows produced reasonable valuations within two years of market extremes. The problem is locking in dismal long-term returns near bubble highs.

It’s easy to get pulled in by bearish news when things are going down. It can be hard to be optimistic. But it’s important to be realistic. Looking at valuations and some rough math to try and be ‘roughly right’ and not ‘precisely wrong’ can be helpful. In the end, you also need to invest with a process that you can stick with through the ups and downs—whether that’s with a conservative or a more aggressive allocation process.

But if it’s true that, even after the recent drop, we’re looking at an expected return in the S&P 500 somewhere between 0% and 5.25% per year over the next decade, there are many stocks with after-tax free cash flow yields between 5% and 7%. Many of those companies have competitive advantages which make them highly likely to be making more money 10 years from now than they are today, and that will allow them to at least keep up with inflation. It takes some effort to do the work in determining the sustainability and likelihood of those earnings, but if you do it and are correct, there are portfolios that you can put together to both outperform the market and keep up with inflation over time—even if it’s not easy. As Charlie Munger has said in the past: “It’s not supposed to be easy. Anyone who finds it easy is stupid.”

There are no certainties in the investing business. Much of the above is mere opinion and speculation from me and others. So, as always, treat it as information and entertainment, not as investment advice of any kind.